Human Nutrition and Digestion

Humans need to consume a balanced diet in order to stay healthy, in which all the food groups are obtained in their appropriate proportions. Eating a high-fat diet can result in obesity and coronary heart disease, while a lack of certain food groups can result in malnutrition and deficiency diseases such as scurvy, rickets and anaemia.

Food groups and their functions

Carbohydrate: source of energy. Carbohydrates consist of many sugar molecules joined together. Digestion of carbohydrates releases sugars such as glucose, which are used to release energy in respiration. Sources of carbohydrate include potato, rice, sugary snacks, pasta and vegetables.

Protein: growth and repair of cells. Proteins are made up of long chains of amino acids which are used to build protein molecules within our own bodies to create cellular components. Foods rich in protein include fish, meat, eggs and beans.

Lipids: energy store and insulation. Lipids have a bad reputation but play important functions in our body when consumed in small amounts. They insulate brain cells and help nervous impulses to travel more quickly through our nervous system. They also form an insulating layer beneath our skin to prevent heat loss and form an important store of energy. Sources of lipids include butter, olive oil, cheese and nuts.

Scurvy is a deficiency disorder caused by a lack of vitamin C. The disease was mainly associated with pirates and sailors due to the lack of perishable fruits on-board ships.

Vitamin A: needed for good vision, healthy skin and a strong immune system. Vitamin A can be found in dairy products and oily fish. Vitamin A deficiency can cause blindness and is one of the biggest causes of preventable childhood blindness in the developing world. Genetic modification of wild rice species to produce new varieties of rice with increased vitamin A content is one of the measures taken to prevent vitamin A deficiency.

Vitamin C: needed for wound healing and the formation of connective tissue. It can be found in citrus fruits and leafy green vegetables. Vitamin C deficiency can cause tiredness, gum disease and bleeding from the skin. It was a common ailment among sailors before the 18th century due to a lack of fresh fruit onboard ships.

Vitamin D: needed for healthy bones and teeth. Our bodies synthesise vitamin D when exposed to sunlight but we can also obtain it from our diet in foods such as eggs and oily fish. Vitamin D deficiency leads to rickets (deformity of the bones) and bone pain.

Calcium: needed for healthy bones and teeth, for blood clotting and muscle contraction. Sources of calcium include milk, eggs, cheese and leafy green vegetables. Calcium deficiency can lead to weak teeth and bones, muscle spasms and poor blood clotting.

Iron: iron is a component of haemoglobin in our red blood cells so it plays an important role in the blood’s ability to transport oxygen. It can be found in leafy green vegetables, red meat, beans and nuts. A lack of iron causes anaemia, which is characterised by tiredness due to reduced oxygen transport in the blood. Women are more susceptible to anaemia due to the monthly loss of blood during menstruation.

Water: water is an essential component of our diet as it forms a component of the cell’s cytoplasm, where many chemical reactions occur. Water is obtained both in food and drinks and is also produced as a by-product during respiration.

Fibre: fibre is a component of food which cannot be digested and is found in food, vegetables and cereals. It aids the movement of food through our gut (peristalsis) and a lack of fibre can result in constipation.

Energy requirements

The amount of energy we need to obtain from food varies from person to person. Energy needs mainly depend on:

Age - energy needs increase from childhood to adulthood, then decrease again towards old age

Activity levels - people who use more energy will need to obtain a larger amount of energy in their diet. For example, an athlete will need to consume a larger amount of calories than an office-worker

Pregnancy - people of a higher mass require more energy. Pregnant women have a larger mass so need to obtain a higher amount of energy from their diet

Digestion

Large food molecules need to be broken down into smaller ones to be absorbed by the villi in the small intestine. Enzymes catalyse the breakdown of food molecules and increase the rate of reaction at body temperature.

Amylase is responsible for the breakdown of starch into a two-sugar molecule called maltose. Another enzyme called maltase breaks this down further into glucose, which is a single sugar molecule. Starch breakdown occurs as soon as we place food in our mouth, as amylase is present in our saliva. Amylase is also produced by the pancreas and small intestine.

Proteases are the name given to a group of enzymes which can breakdown protein into amino acids. A specific protease is called pepsin which is found in the harsh, acidic environment of our stomach, where most of the protein we consume is digested.

Lipases are the enzymes which break down lipids into fatty acids and glycerol. Lipases are produced by the pancreas and small intestine.

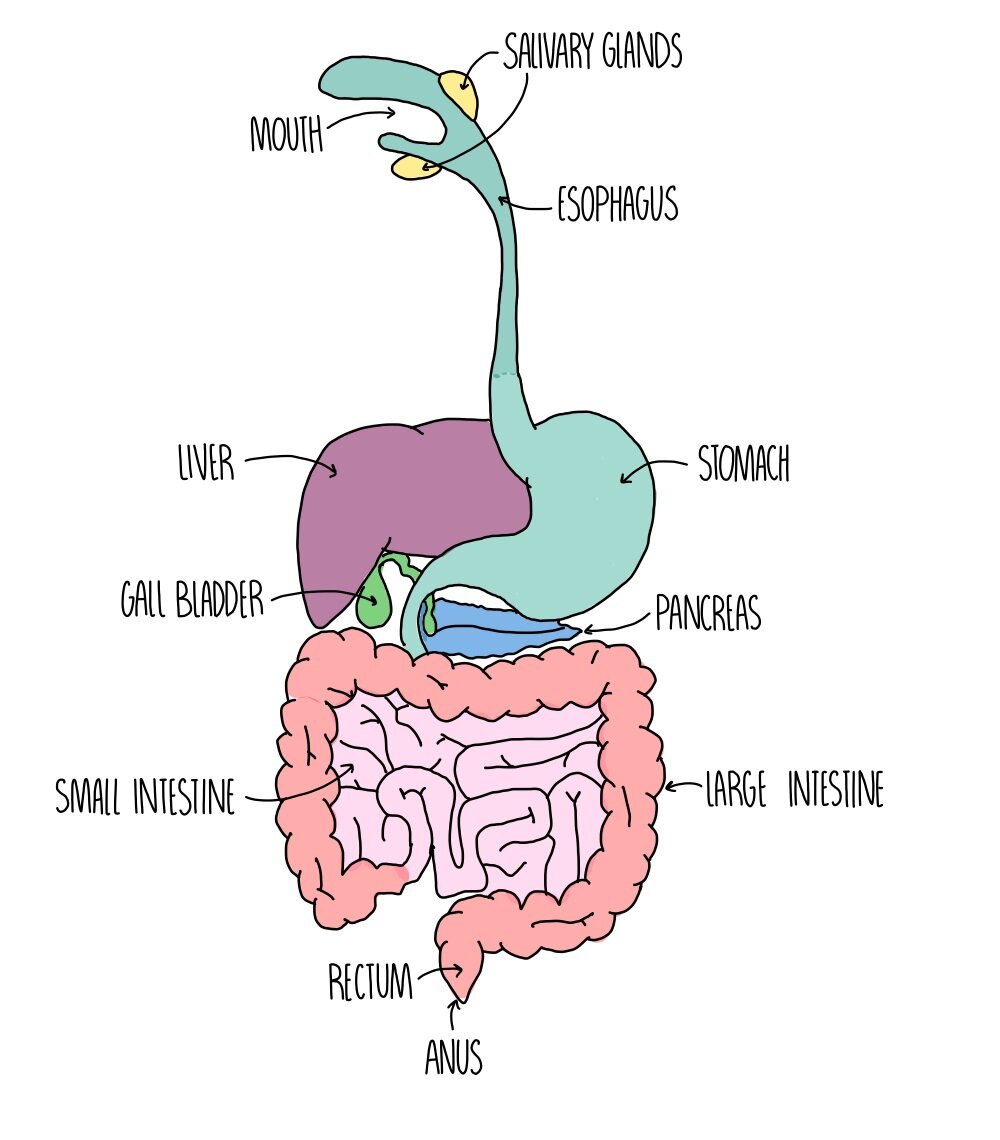

Organs of the alimentary canal

Food begins its journey through the alimentary canal (the digestive system) in the mouth. Even at this early stage, carbohydrate is already being broken down by amylase enzymes present in our saliva. Chewing breaks up food, increasing the surface area for the digestive enzymes to act on. A structure at the back of our throat called the epiglottis prevents food from being inhaled through our windpipe during eating. Once we swallow, a muscular tube called the esophagus moves the food into the stomach.

The stomach contains pepsin, an enzyme which breaks down proteins into amino acids. The stomach is filled with gastric juices containing hydrochloric acid, which provide optimal pH conditions for pepsin to work effectively. The stomach has a protective lining to shield the stomach wall from the corrosive acids and damage to this lining results in stomach ulcers. By now the unappetising mixture of partially digested food and gastric juices, which we refer to as chyme, is quite acidic. Bile, which is produced by the liver and stored in the gall bladder, neutralises the chyme on its way to the small intestine, and has the additional effect of emulsifying fats to facilitate their breakdown.

Once in the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum, food continues to be broken down, both by enzymes released by the small intestine but also enzymes that are secreted into the small intestine from the pancreas. When digestion is complete, sugars, amino acids, glycerol and fatty acids are absorbed into the bloodstream through finger-like structures called villi which line the walls of the second part of the small intestine, the ileum.

The remaining undigested material travels into the large intestine, which is also composed of two parts - the colon and the rectum. In the colon, water is absorbed into the bloodstream leaving behind the waste material faeces. This is stored in the rectum before removal from the body through the anus.

Adaptations of villi

Villi are adapted in a number of ways to facilitate the absorption of digested food molecules into the bloodstream

Large surface area - millions of villi line the walls of our small intestine. Each of the individual cells even have their own microvilli. If you completely stretched this out, you’d have a total surface area of about 32 square meters, which is not much smaller than the average London flat.

Short diffusion distance - the villi wall is just one cell thick and capillary close to the epithelial layer, resulting in a short diffusion distance

Active transport - the small intestine doesn’t just rely on diffusion to absorb food molecules, but also carries out active transport. The cells contain carrier proteins and lots of mitochondria to provide energy for this process.

Network of capillaries - quickly transports glucose and amino acids away to maintain high concentration gradient for diffusion.

Lacteal branch - transports lipids away from the small intestine

Peristalsis

The movement of food through the alimentary canal is called peristalsis and is controlled by two groups of muscles, circular and longitudinal muscles.

Contraction of circular muscles reduces the diameter of the gut wall whereas contraction of longitudinal muscles reduces the length of the gut. These muscles work together to produce a squeezing motion, which moves the ball of food (the bolus) through the gut.

Did you know..

Digestive enzymes are a useful cleaning agent due to their ability to break down biological molecules and are commonly found in washing powders and other cleaning products. Even art conservators use spit (a handy source of amylase) to clean dirt and grime from paintings to keep them looking spotless.

Next Page: Nutrition in Plants

Download worksheet: Nutrition in Humans / Answers